By Danielle Goldfarb (RIWI)

Given how long the COVID-19 crisis has lasted, workers are facing a different set of work options and reconsidering the shape of their working lives. New forms of gig economy work have blossomed as part of the work-from-home delivery economy. Workers may be fearful of reentering the workforce in roles that carry a risk of infection. Many people have been laid off and rehired multiple times. Work from home possibilities and flexibility in terms of time and location have become the norm both for piecemeal work and permanent jobs.

A reshaping of economic options is underway and we can see it and feel it all around us. But much of this is not reflected in traditional economic data, putting policymakers at a major disadvantage in supporting workers during the economic recovery.

Traditional indicators collected by governments focus only on one option: whether people have a job. Yet how meaningful is this in 2021’s dynamic economy, as larger swaths of workers, across all economic groups, face a new set of options and may be changing their views of what constitutes the best working arrangement for them?

Both pre-pandemic and increasingly now, globalization and digitization make it possible to sell services and products via online platforms both locally and globally. There are many ways people can and do earn money that don’t involve a job in the traditional sense of working for one employer: Instacart shopper, Uber driver, selling freelance graphic design, or programming services are some examples.

How would you answer the question of whether you have a job if this sort of task-based work is your main income source? Without a good handle on these different work configurations and this reshaping of economic options, how can we capitalize and adapt? This is especially important as we consider the options available to young people entering the labour market for the first time, or those groups that have been hardest-hit by both COVID-19 and its economic effects.

The pandemic represents a different kind of economic crisis because of its length, non-linearity, and reshaping of available options. We need a set of real-time workforce indicators that is more flexible and that complements our traditional ones.

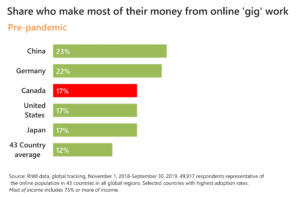

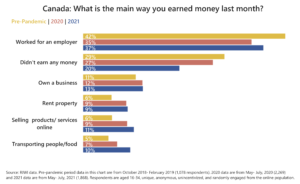

One idea is to ask people not only whether they have a job, but what are the main ways they earn money and whether their ways of earning money include specific types of online platform economy work. 1 We did this in a multi-country study pre-pandemic (chart above) and continue to collect these data during the pandemic (see chart below). In addition to more traditional questions about whether people are employed or looking for work, we asked people both how they earn money and about specific types of online platform work.

Typical survey techniques make it difficult to access a diverse array of immigrants and young people – both critical groups for this topic – and so we at RIWI used an approach that randomly engaged anyone from the online population in each country. We also did so without gathering any personally identifiable information to maximize the chances that the most diverse group would participate.

We found that:

- Both before and during all stages of the pandemic until now, a non-trivial share of citizens of working age is deriving a significant share of their income from gig economy work via online platforms.

- Most do this kind of work because they enjoy it, but a significant share had no better available alternatives.

- Looking more closely at Canada’s young people, for example, we find there is notable movement away from traditional employment as a main income source towards categories such as transporting people and food via online platforms as the pandemic continues.

Will young people just out of school take up gig work as a primary form of income? What are the implications of this? What will happen as social support winds down?

Globalization and digitization had already opened up new labour market possibilities and pressures pre-pandemic. The pandemic has and will continue to further reshape traditional labor market options in real-time. To set up citizens to succeed, policymakers need to understand the true range of options workers face during each of the next phases of the pandemic and recovery.

(Adapted from submission requested by the Ontario Workforce Recovery Advisory Committee)

Footnote

1 This approach is based in NBER research from Abraham and Amaya on Amazon Mechanical Turk workers which finds that asking about other ways of earning money increased the number of people participating in the workforce and the number of multiple job-holders. Probing encourages respondents to mention informal and alternative work activities in their employment-related responses, and suggests current measures likely do not accurately capture the range of ways in which people work. https://www.nber.org/papers/w24880