Summary:

Stigma directed toward people who use drugs, those with substance use disorders, and those identifying as in recovery from addiction is a public health crisis.

In an effort to inform the most effective stigma reduction efforts and reduce overdose deaths we delivered an anonymous Web-based survey to measure perceived societal stigma among over 26,000 Americans.

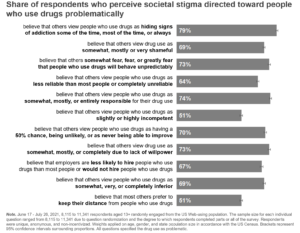

We found alarmingly high levels of perceived societal stigma:

- 71% of respondents believed that society at large considers individuals who use drugs problematically to be outcasts or non-community members

- 74% of respondents believed that society at large views individuals who use drugs problematically as somewhat, mostly, or entirely responsible for their drug use

- 73% of respondents believed that society at large views individuals who are dependent on drugs as having moderate, low, or no chance of maintaining recovery

Moving forward, we aim to explore the impact of stigma on the policies and practices that continue to challenge our response.

The Problem:

The US continues to experience an unprecedented overdose crisis that is multi-faceted, complex, and resistant to many well-intentioned strategies (1). Although significant progress has been made in understanding substance use disorders as a chronic and treatable disease (with recovery as the expected outcome), overdose deaths in the US still continue to rise to historic levels — over 94,000 drug-involved overdose deaths reported in 2020 alone (2).

Stigma — negative attitudes and behaviors aimed at individuals who are associated with a specific social group and/or status — is deeply discrediting and experienced as labels, stereotypes, status loss, and discrimination (3). Stigma creates a power dynamic that exploits, controls, and excludes individuals, often in subtle ways that are indirect and hidden within cultural norms (4). Stigma directed toward people who use drugs, those who use drugs problematically, as well as those who are in recovery from drug addiction, continues to be a significant barrier to America’s response to drug use (1; 5; 6) and the overdose crisis.

Stigma directed towards people who use drugs is prevalent across countries (7), including in the US, where stigma directed towards people who use drugs is even more pervasive than stigma directed toward people with mental illness (8; 9). Stigma associated with drug use can negatively impact:

- treatment by others (10), including healthcare system workers (11; 12),

- willingness to seek help, engage in, and complete treatment programs (13; 14; 15),

- willingness to access and utilize evidence-based medications (16; 17), and

the ability to garner public support for programs aimed at addressing problematic drug use (18), including harm reduction services (19; 20), one of the most effective methods of mitigating risk and supporting people who use drugs.

Research Aim:

Much previous work has focused on specific components of stigma (for a review, see 21). Researchers have assessed stigma toward people who currently use substances problematically (i.e., disregarding those in recovery; c.f., 22), stigma toward medications for opioid use disorder (23; 24), stigma among college students (25; 26), stigma delivered by healthcare professionals (e.g., 12), and the stigma experienced by individuals who identify as having a substance use disorder and/or as being in recovery (e.g., 27; 28), among other important lines of research. We sought to extend previous work by measuring multiple components of stigma directed towards people who use drugs, those with substance use disorders, and those identifying as in recovery from problematic drug use across the US, and among a large, diverse population of respondents. Our study goes beyond traditional samples to gauge population-level perceptions of stigma, including perceptions of preferred social distance, character, and attributions. Thus, our insights are highly generalizable and informative for intervention development and policy creation. Ultimately, this research serves as a first step in the exploration of stigma across the US and around the world, the measurement of changing stigma over time, the identification of predictors of stigma, and the development of and support for effective stigma-reduction interventions.

Key Findings:

Using RIWI technology, we surveyed a random sample of over 26,000 Americans to gauge their perceptions of stigma among society at large. Leaning on previous, validated measures of drug use stigma (29; 30), we created a face-valid survey instrument measuring diverse components of perceived stigma. Perceived societal stigma (as opposed to personally endorsed stigma) was chosen for the first phase of this research program to minimize the effects of social desirability bias on responses. The sample size for each individual stigma question ranged from 5,429 to 11,341. This range is due to question randomization and the varying degree to which our non-incentivized anonymous respondents completed parts or all of the survey. To estimate national levels of perceived stigma, we applied weights on gender, age, and state population size in accordance with the US Census (for more information, see detailed methodological statement below).

Across all individual stigma items, over half of respondents perceived stigma among others (see figure below). Seventy-one percent of respondents believed that most others view those who use drugs problematically as outcast members of their community or not as members of their community at all. Stigma directed toward people who use drugs problematically extended to those who identify as in recovery from problematic drug use. Seventy-three percent of respondents believed that society at large views people who are dependent on drugs as having moderate, low, or no chance of maintaining recovery. Twenty-eight percent of respondents personally believe that a person who takes medication for their addiction is always in recovery.

Call to Action:

Our findings demonstrate that stigma directed toward individuals who use drugs problematically and those who identify as in recovery from problematic drug use is pervasive in the US. Indeed, we observed high levels of stigma that are comparable to those observed in previous research using nationally representative samples (e.g., 9). Negative perceptions about people who use drugs, addiction and recovery are fundamental barriers to expanding wellness opportunities and a significant driver of the overdose crisis. In order to create effective interventions that address stigma, we must gain a deeper understanding of stigma perceptions across regions and among the most diverse set of respondents. This project aims to develop a large repository of stigma sentiment data and dismantle the structural barriers that impede our response to the overdose crisis. As this project evolves we will continue to share insights on perceived stigma across the United States, including findings on the relationships among stigma indicators and on regional and demographic differences in perceived stigma (e.g., perceptions among healthcare professionals).

We believe it is crucial to collect and measure granular-level data to more deeply contextualize stigma, affect change, and ultimately save lives. We are seeking partners from academic, government and private institutions to collaborate with and use this information to understand and remove the fundamental barriers stigma generates. For more information or interest in partnering, please email Sean Fogler (RIWI) and Bill Stauffer (PRO-A).

Methodology Statement:

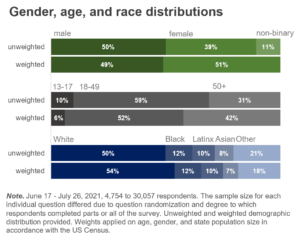

We used RIWI’s Random Domain Intercept Technology (RDIT) to reach a random sample of US Web-users between June 17 and July 16, 2021. RIWI respondents randomly encountered the survey while browsing the Web. Upon encounter, respondents could opt-in to participate in the survey. RIWI surveys are fully anonymous and do not collect any personally identifiable information, there are no incentives that may bias responses, and respondents may leave the survey at any time (30,057 respondents opted-in; 16% completed the entire survey). During data collection, data are delivered to partners real-time via a secure interactive dashboard. Data weights were applied on age, gender, and state population size in accordance with the US Census. The final weighted sample excluded those who identified as non-binary (n = 3,167), resulting in an initial base sample of 26,890 respondents (17% completed the entire survey). For the current report, we implemented an available case analysis (in other words, we utilized the full respondent set on each question, and did not limit analysis to only those who completed the entire survey).

Respondents had to be 13 years of age or older and located in the US to participate. We reached a diverse set of respondents on gender, age, and race (see figure), as well as political affiliation, urban/rural-dwelling, annual household income, religion, education, and employment. We also asked respondents to indicate whether they had an addiction, used drugs, were in recovery from addiction, were a family caregiver of someone with addiction or who was in recovery, had a close friend or family member with addiction or who was in recovery and/or were a professional care provider to persons with addiction or who were in recovery.

Image Credit: Timon Studler licensed under Unsplash