By Danielle Goldfarb

This article was originally published in Maclean’s Magazine on June 4th, 2020.

Canada and the U.S. release their official jobs reports on June 5, telling us what happened to jobs by mid-May. If these jobs reports are anything like last months’ reports, they will provide deep insight into what happened during the lockdown period, and continue to confirm what we all see around us: there has been a dramatic shock to the Canadian and U.S. labour markets and economies.

But by the pace of the COVID crisis, these data are now ancient history. What matters now is what has happened since the early stages of reopening began later in May and what will happen as businesses assess true consumer demand in the days ahead. Will more workers be let go? Are workers who were furloughed or part-time being brought back on again? The jobs report won’t tell us that until July, which is too late for policy makers, forecasters, and business leaders that need to make decisions now. The federal government, for example, needs to determine whether and how to extend income and wage supports that will start to soon run out.

This is just one of the limitations of the official jobs data during COVID, but it is one that we can fix. To make effective and agile policies in the next phases of managing the COVID crisis, here are some adjustments we should make in our thinking about the headline jobs report:

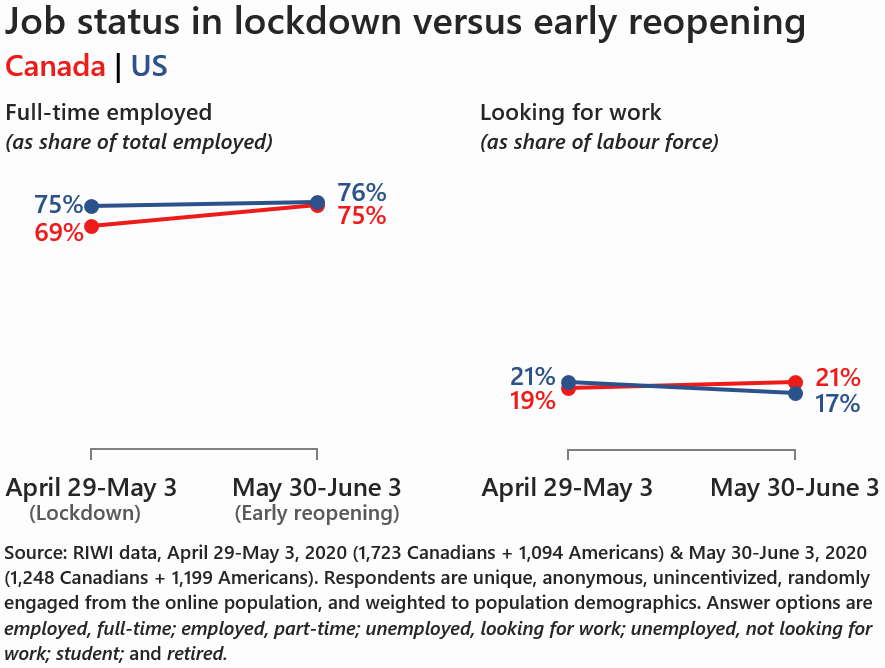

1. Look at how Canadians’ job status is changing daily. Employment is usually a lagging economic indicator. But in this crisis, real-time jobs data may actually provide a leading indication of how quickly or slowly economic activity is coming back on stream. For example, in the last week of May, there was a notable improvement in new job postings on Indeed.ca, the job search website, relative to the same week last year, suggesting some momentum in the jobs market. At RIWI, we ask more than 1,000 unique, randomly engaged Canadians about their working status on a continuous basis every week. When we asked this over May 30 to June 3 as provinces began reopening, we found that more than one in five Canadians who want jobs don’t have them, an increase relative to just under one in five during the same period in the previous month when we were in lockdown. However, full-time employed Canadians as a share of total employment grew from 69 to 75 per cent across these two periods, indicating that a growing share of those working part-time hours during lockdown returned to full-time work.

2. Look at what happens to incomes, not only jobs. This is because asking people if they had a job last week, as the official measures do, does not capture the full range of ways in which people earn money today, including those that drive for Uber or sell freelance services on TaskRabbit. We are in the midst of the first major economic shock to hit Canada since such digital platform gig work became possible. So we need to include these types of activities — not just traditional jobs — when we consider the full impact on Canadians’ livelihoods. RIWI data on income loss show that as of June 3, more than one in three Canadians — and nearly half of Canadians aged 25 to 34 — have lost half or more of their income. The headline jobs data alone understate the true extent of the income loss Canadians are experiencing. As leaders contemplate whether to extend or wind up income support as reopening continues, we will need to monitor changes to income and hours of paid work (which is included in the official jobs reports) in real-time.

3. Think at least as much about psychology as about actual economic conditions. As the economy reopens, do Canadians feel safe going out to a restaurant or to a crowded elevator in their workplace? Will parents feel comfortable sending their kids to school and camps if and when they reopen? Will Canadians hesitate to spend if they believe this crisis will be deeper and longer-lasting than the conditions suggest? Behavioural fear is the X-factor in this (or any) crisis. If we don’t measure behaviour, inclinations and attitudes well and as they change during different phases of the pandemic, we can’t model these variables in our forecasts, or address them in policymaking. We can look, for example, at OpenTable’s Canadian reservations data as reopening proceeds (right now, they show a slight improvement in the past week relative to the previous week).

4. Prepare for secondary economic shocks. Government income supports have kicked in, and many of those let go during the lockdown expect to be rehired now and in the weeks ahead. But what happens once government support winds down and if businesses do not reopen and rehire their workers? Economist Frances Donald calls this the “economic second wave.” Of course, there will also be jobs impacts if leaders need to halt or reverse reopening due to new outbreaks. The upcoming official jobs reports will cover these impacts in the rear-view, but policymakers need to both plan for them and then monitor their severity in real-time.

When we go beyond what we’re likely to see in this week’s headline jobs numbers to monitor a fuller set of economic but also psychological impacts in real-time, we see some very small, early steps towards part-time work becoming full-time but still a growing share of those who want jobs without them and a significant share who have lost a substantial part of their livelihoods. How this will evolve in Canada – and in the US where reopening is taking place amidst a growing protest movement – is unclear. What is clear is that we will need to understand Canadians’ fears and anxieties and not only their job status today if we are to successfully navigate the economic crisis.