By Armine Yalnizyan and Danielle Goldfarb

Armine Yalnizyan is an economist and the Atkinson Fellow on the Future of Workers. Danielle Goldfarb is Head of Global Research at RIWI.

This piece was originally published by Maclean’s on April 21, 2020.

COVID-19 is a health crisis that has triggered an economic crisis which threatens an insolvency crisis. The pace and targeting of public health measures and emergency economic response policies, as well as the impact of re-starting normal activity, will determine whether the fall-out feels like a shorter-lived natural disaster or a cascade of catastrophes, with long-lasting effects.

In the face of so much uncertainty, Canadian policy makers are grappling with a subtle but critical dilemma: they are not armed with the best arsenal of data to help navigate disaster and avoid collapse. But it is possible to gather better data and do so immediately.

The policy-making of the past several weeks has largely occurred in the absence of timely official statistical measures. The data we do have is old by the time the decision-makers see it. How do we know if we’ve got the right information to deal with what changes so swiftly? And will stale-dated data jeopardize optimal timing of critical policy course corrections?

The latest releases from Statistics Canada in the past days show a massive GDP contraction rivalled only by the Great Depression, and breath-taking job losses in March alone. Those early statistics are likely just the tip of the iceberg.

While official sources must be our information anchors, they inevitably provide insights through the rear-view mirror. Just as many big businesses use real-time data to understand and adjust their operations, so the truly enormous business of governing in a pandemic should tap into the timeliest insights to direct swiftly evolving public policy.

We are now heading into the next phase of the outbreak without clarity on whether and when physical distancing measures will intensify or lessen. In order to optimally adjust, improve and target public health and economic policies, we need daily data on COVID-19’s impact on Canadians’ livelihoods, financial well-being, fears and behaviours to watch how each of these subtly evolve, and in turn shape economic and social realities. Behavioural fear is the ‘X-factor’ in any crisis. Its presence or absence is impossible to model in forecasts without real-time data. People behave in unexpected ways when lives and livings hang in the balance. Anxieties can trigger or immobilize action. Concerns can postpone or impede the resumption of “normal” work and leisure. At the same time, lack of concern can compound unintended consequences, too.

We need to quickly begin monitoring not just the public health aspects of the pandemic, but also the mental health dimensions, as well as the economic and social fallout. We must also maintain this scrutiny over the next 12 to 24 months. Our policy-makers require data that goes beyond job loss to include reliable, ongoing measures of income deterioration, especially in the so-called gig economy, as well as trends in the dynamic financial anxiety that shapes consumer behaviour at different phases of the pandemic.

We believe daily tracking is the way to go, something the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis has already started. That bank’s wide-ranging data collection exercise uses COVID-19 Impact surveys to track physical and mental health, as well as social and financial well-being.

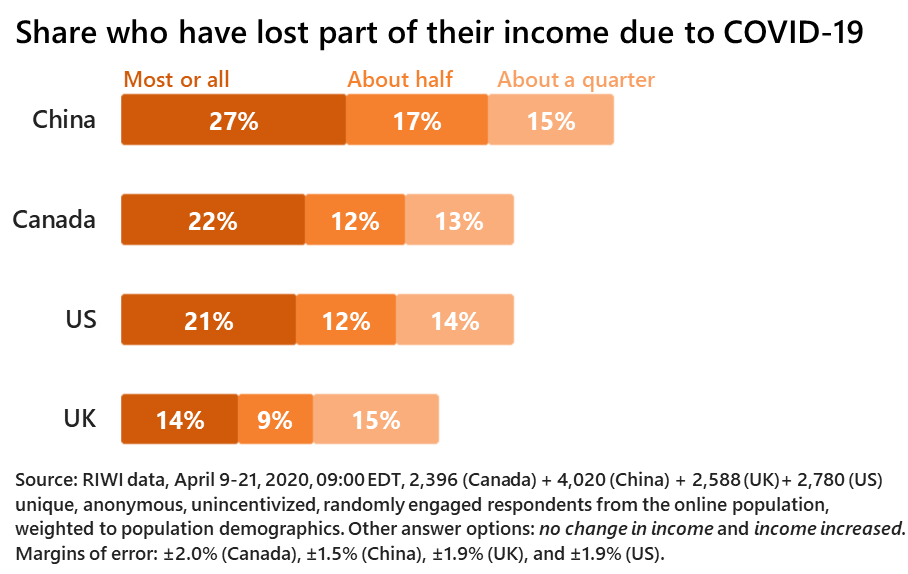

This is a call for more data, which could be supplied in any number of ways. One example (and this is not a sales pitch) is RIWI’s continuous random sampling of the on-line population since mid-March. RIWI’s survey tool, which is able to monitor daily changes in compliance with public health directives during outbreaks as well as labour market and consumer behaviour around the world, reveals that that Canadians have been remarkably hard-hit economically by COVID-19,and slightly moreso, surprisingly, than our American counterparts.

What can more timely data tell us? Since the job market report, RIWI survey responses suggest Canada’s unemployment rate rose to 22 per cent by April 21 (mirroring a similar outcome in the U.S., where researchers used a similar technique). Worse: by mid-April, 22 per cent of Canadians reported that they had lost all income due to COVID-19, and an additional 12 per cent said they’d lost up to half.

To assess the full scale of the economic fallout, we need to know about income loss as well as job loss, which Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey does not do. This detail is particularly relevant for people working for multiple employers or gig workers who also tend to be younger and worse paid than typical wage-earners. Loss of even a few hours of pay can be devastating for workers barely patching together a living. Official statistics didn’t give us a very clear picture of how many such workers there were before the crisis, nor how COVID-19 was changing things.

The RIWI survey shows that, by mid April, two in five Canadians reported they couldn’t last more than a month if they lose their income. Two in five respondents said they didn’t have access to paid sick leave and couldn’t stay home if they got ill. Two-thirds said any cash from the government would go straight to covering basic needs. These data show that support needs to extend far beyond the one million people that the LFS said lost jobs on April 9. They illuminate how the emergency economic response measures that have been frequently adjusted may need to continue to be tweaked to reach the extraordinary number of people who need help, even though the majority of Canadian workers still have their job and income.

The path to recovery is not obvious. What proportion of unemployed Canadians might be able to return to what they were doing before March 15? Will a prolonged period of uncertainty and fear lead to a more permanent re-shaping of the economy? Will people save more? Go out less? Travel infrequently? How many households and businesses lose everything because of pre-March 15 debt that they cannot repay or extend? Governments, business and the non-profit sector need timely answers to these questions. They could have the means to do it. The combination of official statistics and daily soundings offers a robust tool-kit for decision-makers.

To Statistics Canada’s credit, the agency is putting out new types of surveys to capture social and economic impacts of COVID-19. They are short and easy to understand, which is critically important at a time when many Canadians are contending with information overload. But if we rely only on episodic data collection, we will miss important daily inflection points, or fail to anticipate or observe important psychological shifts related to the pandemic that drive consumer or labour market behaviour.

In a crisis that moves as swiftly and unpredictably as the COVID-19 pandemic, we need to track financial impacts and behavioural changes on a daily basis.

Agile policy demands agile data. Let’s use all the tools we have to steer quickly, with confidence, to the other side of the pandemic.

Related research:

Could a fear-demic lead to an unnecessarily severe economic crisis?

Hearing from all voices during COVID-19

Are enough of us doing the right thing? Physical distancing during COVID-19

Virtual lecture: How is the public responding to COVID-19?

Chinese vs. American Confidence in COVID-19 Response Measures