By Jonathan Mellon and Chris Prosser

As the EU referendum approaches there is little that the Remain and Leave sides can agree on. One thing most people can agree on is that young people are central to deciding the outcome of the referendum. Young people are both the Remain campaign’s greatest asset and their greatest liability – they are far more likely to support Britain’s continued membership of the EU, but they are also much less likely to actually turn out to vote on the day. Unsurprisingly, young people have been the focus of much attention during the referendum campaign.

Despite their importance, the likely behaviour of young people at the referendum is particularly hard to predict because they are one of the most difficult groups to poll. The impact of this difficulty can have drastic effects on political polls. In 2015, polling firms confidently predicted a hung parliament, with Labour being the most likely to form the next government. Instead, the Conservatives finished with a comfortable lead and a majority in parliament. Subsequent investigations have pointed to the difficulty in gaining representative samples of young people as one of the key causes of this miss.

The problem in 2015 was that young people were very unwilling to take part in polls. As a result, the few young people who are successfully contacted to take part were disproportionately interested in politics and likely to vote. This led polls to over-represent young voters and underrepresent young non-voters, skewing the political balance of polling samples.

Since 2015, polling firms have made efforts to try and include more disengaged young people in their polls and weight their samples to look more disengaged. These fixes are clearly important but it is unclear how much this fix is actually improving the underlying samples or simply making them look better on the outside. Both phone polls and Internet panels still appear to under-represent politically disengaged young people in their initial samples. This raises the question of how we might be able to gather samples of young people that are more representative of their levels of political attention, given the challenges faced by traditional polling methods.

To try and get a more representative sample of young people, we have worked with RIWI Corp., a global survey technology company that captures citizen and consumer opinion in all countries. ⎼RIWI’s approach of Random Domain Intercept Technology (described in this patent)⎼ works by targeting Web users, anywhere in the world, who are surfing online by typing directly into the URL bar. When these users make data input errors by typing in websites that no longer exist, or by mistypes on non-trademarked websites that RIWI owns or controls, RIWI invites these random users, filtered through a series of proprietary algorithms, to participate in a language and geographically appropriate survey. Participation in any RIWI survey is voluntary and anonymous. More detail on the global RIWI survey system, which collects no personally identifiable information and whose technology and data in more than 200 countries can be found here and in this journal article.

In this post, however, we look simply at the nature of the RIWI sample for respondents aged 40 and under. We ran a short RIWI survey on the EU referendum from 2016-03-11 to 2016-06-09, receiving 7444 partial responses from people under the age of 40.

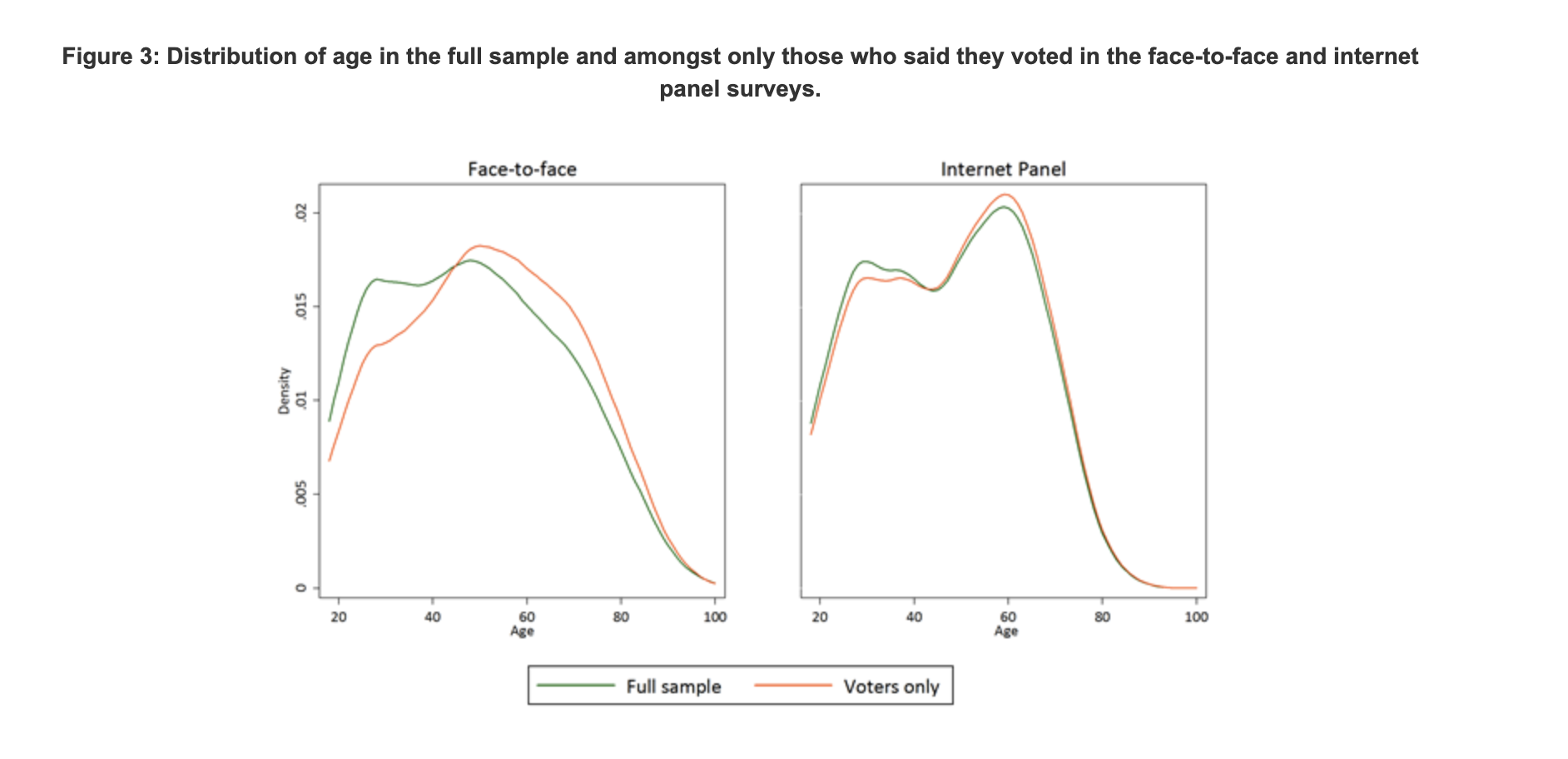

So can internet intercept surveys find disengaged young people? To answer this, we compare the self-reported turnout in the 2015 General Election of young people in the RIWI sample to the gold-standard British Election Study (BES) face-to-face survey that was conducted immediately after the election.

Figure 1 shows the self-reported turnout rates for respondents in the face-to-face British Election Study and the RIWI survey. For comparison, we also show the relationship between age and turnout for respondents in the BES Internet Panel that was conducted using YouGov Internet panels. Using the unadjusted weights (that reflect polling methodology prior to May 2015), turnout for young people is far too high at all ages. By contrast, the RIWI survey shows a relationship between age and turnout that is much closer to that seen in the BES face-to-face survey. This suggests that the RIWI method is effective at naturally contacting politically disengaged young people compared to standard methodologies. It should be noted that the reweighted BES Internet panel (that reweights the data using a similar approach to those pollsters have used since 2015) also shows a similar relationship between age and turnout. However, this relies on post-hoc adjustments rather than capturing disengaged respondents in the original sample.

[Above Graph:Turnout by age for different survey approaches.]

Of course our new Internet sample gathered through RIWI technology is not perfect. While RIWI does seem to capture a more politically representative sample of young people than other pollsters, it does still over represent people with degree qualifications compared to the BES face-to-face survey. This highlights the ongoing difficulties with surveying representative samples of less educated and working class respondents.

With these caveats in mind, what do young people in our sample think about the EU referendum and how many of them are likely to vote? We asked respondents how likely they were to vote on a 1-5 scale. Using a model predicting validated turnout from the 2015 BES Internet Panel, we assigned a probability of voting based on these responses. We then reweighted the vote intentions of the RIWI responses based on their likelihood of voting.

Across respondents aged 40 and younger, 61.6% of young voters intend to vote to remain in the EU. There are approximately 19 million people aged between 18 and 40 in the UK. If all of them voted in the referendum that would result in an approximately 4.4 million vote lead for Remain over Leave amongst young people. However, this does not account for non-voters. More than half (50.2%) of young people in the sample will not vote in the EU referendum based on our modeling. After accounting for non-voters, Remain looks likely only to have a 2.2 million vote lead among young people. Whether this number is enough to counterbalance the votes of older people, who are more likely to turnout to vote, and more likely to vote to leave when they do, remains to be seen. Our results suggest that the Remain campaign is right to worry about weak turnout among young voters.

Given the increasing difficulties in contacting disengaged sections of the population, pollsters may need to move beyond relying on a single source of respondents. RIWI could potentially provide access to some hard to reach respondents, such as politically disinterested young people. Perhaps the argument in the polling community should not be about whether phone or internet polls are ‘better’ but how the advantages and disadvantages of different polling methods might be combined to produce more accurate estimations of what the population really thinks.

Jonathan Mellon is a research fellow at Nuffield College, University of Oxford working with the British Election Study. His research focuses on survey methodology, long term changes in British politics, and anti-immigrant attitudes. He also works on the BBC’s election night coverage as a psephologist and at the World Bank studying citizen engagement across countries.

Christopher Prosser is a Research Associate in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Manchester and a non-stipendary Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford, working with the British Election Study. His research focuses on political behaviour and party competition in Britain and Europe, EU referendums, the effects of electoral systems, and survey research methodology. He also works as a psephologist for ITV.